The September 2023 issue of the latest in financial #AdvisorTech kicks off with the news that WiserAdvisor, one of the longest-running lead generation services in the industry, has acquired IndyFin, a startup advisor rating platform that had aspired to be the “Yelp for Advisors.” On the one hand, that provides WiserAdvisor with an opportunity to jump into the business of client reviews and ratings, which has garnered significant interest from multiple AdvisorTech startups hoping to promote such services in the wake of the SEC’s new marketing rule allowing client testimonials. On the other hand, it raises questions about how much demand there really is for a stand-alone advisor rating tool, since few advisors are likely to accumulate enough ratings from current or former clients to actually draw in new clients (and advisors with enough clients to get a critical mass of reviews likely have enough clients that they can just rely on client referrals … or don’t even need to add new clients anymore?).

From there, the latest highlights also feature a number of other interesting advisor technology announcements, including:

- Former United Capital Partners founder and CEO Joe Duran is reportedly exploring the launch of a new RIA four years after selling his firm to Goldman Sachs, with a reported emphasis on providing lead generation opportunities for advisors on its platform. If successful, that could provide a new model for boosting organic growth without the high cost of outsourcing to a third-party lead generation service or relying on inorganic growth via mergers and acquisitions.

- Onramp Invest, the platform that aimed to solve the challenges of cryptocurrency investing for financial advisors, was acquired by Securitize, a platform specializing in blockchain-based tokenization of private market investments, suggesting that advisors’ interest in recommending digital assets for their clients — already limited during previous rallies in the price of bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies — has declined further amid the price crash and scandals that have happened in the year-plus since

- Wealthtender, a lead generation and advisor rating service, has announced a partnership with custodial account provider UNest to bring its find-an-advisor technology to UNest’s customer base of parents opening investment accounts for their children. While expanding Wealthtender’s footprint in the competitive lead generation market, that raises questions about how large of a potential customer base UNest can provide (and whether Wealthtender will be able to secure any larger enterprise partnerships that can help it secure a spot as the “one and only” advisor rating service)

Read the analysis about these announcements in this month’s column, and a discussion of more trends in advisor technology, including:

- With AI technology proliferating in the financial services industry, regulators are increasingly concerned about possible conflicts of interest if the technology can be manipulated to recommend a company’s products and solutions over others (despite being under a technological veneer of “objectivity”). That was highlighted most recently by the SEC issuing proposed regulations for RIAs for evaluating and eliminating conflicts of interest in their technology, and Massachusetts Secretary of State William Galvin sending a request for six companies from different areas of the industry to detail their use of AI in their business practices

- Over the last 10 to 15 years, a number of AdvisorTech providers have gained the majority of market share in certain core categories like financial planning and CRM. But as the most recent Kitces Research on AdvisorTech has found, a new crop of tools has arisen in more recent years that have garnered higher satisfaction ratings than the incumbents, and have been steadily gaining market share — suggesting that the traditional advisor tech stack might eventually be upended and replaced by a new, next-generation tech stack that reflects the growing shift of advisors into deeper financial planning and non-AUM fee models

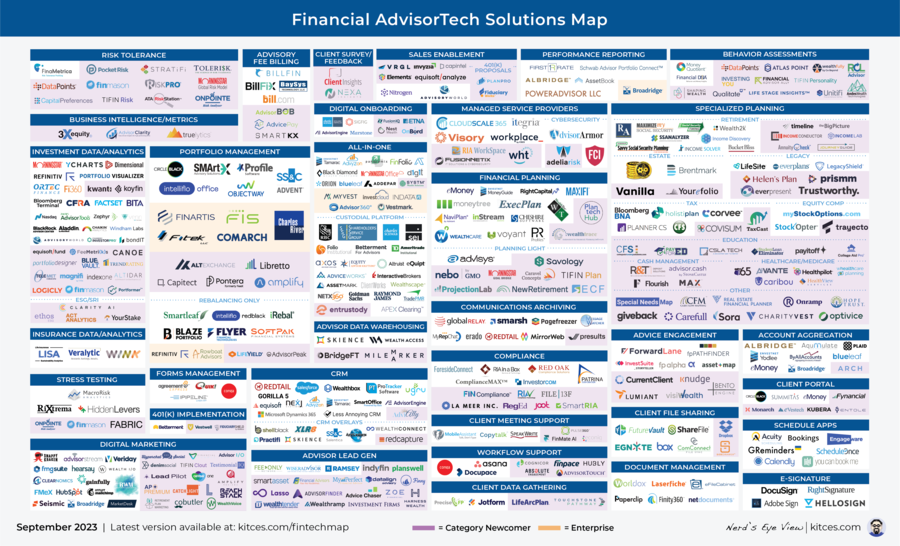

Be certain to read to the end, where we have provided an update to our popular Financial AdvisorTech Solutions Map and added the changes to our AdvisorTech Directory as well!

AdvisorTech companies that want to submit their tech announcements for consideration in future issues, please submit to [email protected]!

ADVISOR REVIEW SITE INDYFIN ACQUIRED BY LEAD GENERATION PLATFORM WISERADVISOR

Lead generation is a notoriously difficult challenge for newer and more experienced advisors alike. For advisors getting started, who are often responsible for building their own book of business from scratch, it can take a long time to acquire enough clients to generate sufficient revenue to keep the business going, leading to astronomically high failure rates (with 72% of new advisors washing out in 2022 alone). Those who manage to survive are often the ones who find productive ways to spend their time getting clients; however, as they become more experienced advisors, the increasing cost of the advisor’s time as the firm grows pushes the cost of acquiring new clients higher. Case in point: according to our own latest Kitces Research on Marketing, the median cost of acquiring each new client was over $4,000 for mature firms, rising to more than $7,000 in acquisition cost per client for the most experienced advisors. That’s due to the sheer amount of time that many traditional marketing strategies like networking, content marketing and social media demand, even as the experienced advisor’s time gets more and more expensive.

The struggle to find clients at the beginning, and the high cost and time-intensiveness of traditional advisor marketing strategies as advisory firms become more mature and try to scale their growth, have led to an increasing hunger for technology platforms that can reliably generate leads for advisors. The most popular of these are referral networks of RIA custodians, such as Schwab Advisor Network and Fidelity Wealth Advisor Solutions, which have sent billions of dollars in referrals each year to independent RIAs over past decade. More recently, a growing number of AdvisorTech startups have arisen aiming to satisfy the demand for lead generation, including Zoe Financial, SmartAsset, Harness Wealth, Wealthramp and IndyFin. The typical price for third-party lead generation, originally set by the RIA custodians and largely adopted by the other services as well, seems to have settled at a 25% share of each referred client’s lifetime revenue.

For advisors, the appeal in the revenue share model of lead generation is that it provides a pay-for-results framework: Advisory firms who pay on revenue share don’t risk paying upfront for prospects who don’t convert to clients, and when they do convert referred clients, the advisory firm will by definition have the revenue to pay for them. For referrers, however, the benefits of the arrangement are clear when looking at the long-term economics. With RIAs having client retention rates as high as 97% (which results in an average client tenure of nearly 30 years), the lifetime value of each referred client for the referrer could be as high as 30 years x 25% of revenue = 7.5 times each client’s gross annual revenue. In other words, a single household with $1 million in AUM paying a 1% annual fee for 30 years would have a lifetime value of $75,000 to a referral provider with a 25% ($2,500/year) revenue share (before even factoring in portfolio growth that would likely increase that amount over time).

The caveat is that although the lifetime economics of lead generation are extraordinary, the shorter-term economics are extremely capital-intensive. The lead generation platforms themselves need to attract clients to their sites (and to vet both clients and advisors in a way that ensures there is a reasonable chance for a match), which has its own significant upfront cost for each client. There’s no public data on how successfully lead generation platforms scale their services, but one that “merely” replicates the average advisory firm acquisition cost of $4,000 per client — for clients that generate only $2,500 in annual revenue for the platform — will be cash flow negative for nearly two years before becoming highly profitable for the subsequent 28 years.

These economics may work out for RIA custodians who have the resources to absorb short-term losses in order to reap long-term gains (and in practice would have far lower client acquisition costs because custodial referrals are typically clients the platforms have already brought in for themselves), but a startup third-party lead generation service would need to walk much narrower tightrope as it balanced the need to attract clients and grow market share against the reality that nearly every new client would initially cost more in client acquisition costs than it would generate in revenue. If the service burns through its cash too soon to see its early clients turn a profit for it, and if it can’t attract further capital investment, there would be a lot of pressure on its ability to operate as a sustainable business.

For many lead generation platforms, this balancing act proves difficult, to say the least. An interesting case in point is that of IndyFin. which launched as a lead generation service in 2020 before announcing in 2022 that it was debuting an “Investor Experience Platform” featuring client reviews of financial advisors — taking advantage of the then-new SEC marketing rule allowing client testimonials to position itself as the “Yelp for advisors.” Presumably the hope was that the rating feature would send more leads to (at least, the better-rated) advisors, which would then result in more (and better) client referrals.

But the reality is that, while review sites are effective in many industries, they’re far less likely to be successful amongst financial advisors. Whereas a business like a restaurant that serves 300 to 600 patrons each night can accumulate a critical mass of reviews on its Yelp page even if only 1% of customers bother to leave a review, many advisors only serve around 100 active ongoing clients in their entire career — meaning that with even a 3% review rate, at most they can only hope for a small handful (literally, one to three) of reviews. And ironically, once the advisor has actually served enough clients to generate a critical mass of reviews, they very well may have enough clients that they’re either at capacity and aren’t taking new clients anyway, or at least have a healthy referral network among their own client base such that they don’t need to pay a third-party service to provide them. In other words, the advisors who need referrals the most are those who likely won’t have enough reviews to differentiate themselves from other advisors on the platform, while those who do have the reviews aren’t likely to need outside referrals at all!

In this vein, it isn’t surprising to hear that IndyFin has decided to sell itself to WiserAdvisor, one of the earliest lead generation platforms in the space, which made its mark using Search Engine Optimization (SEO) to lead customers to advisors on its network via investor education articles on its website in the late 1990s and early 2000s (during which time there was limited competition, allowing it to establish and then maintain an SEO-reinforced “content moat” that continues to sustain them to the present day).

From WiserAdvisor’s perspective, the IndyFin acquisition represents an opportunity to invest in advisor review capabilities without building a new platform from scratch, providing a path to leverage the IndyFin reviews system to enrich the depth of the advisor profile pages on WiserAdvisor’s website, offer IndyFin review capabilities to paying WiserAdvisor users to further boost their web presence, and potentially up WiserAdvisor’s SEO game further by leveraging the kind of user-generated content that can come from a (flourishing) advisor review site with clients regularly leaving fresh reviews.

The question remains, however, whether the average advisor will be able to solicit enough client reviews — either on the newly merged WiserAdvisor/IndyFin platform, or on competing lead generation platforms with advisor ratings like Wealthtender — to make user-generated reviews a useful SEO-driven lead generation device. Both because of the challenge of getting any one advisor to a critical mass of reviews (given the challenge again that advisors only work with so many clients over their lifetime, only a portion of them will ever leave reviews, and advisors who have a lot of clients to leave reviews often don’t need or want to pay for third-party lead gen because they simply get client referrals outright), the fact that there are now multiple competing advisor review sites (and if clients split reviews across all of them, none will ever reach a critical mass), and the simple reality that industry-specific advisor review sites must still compete against the more generalist “review sites” that consumers are already accustomed to using (e.g., Yelp or Google Reviews).

The one segment that seems especially conducive to adopting advisor reviews successfully is larger independent RIAs, which can seek to garner a critical mass of reviews not for their individual advisors but the aggregation of all of them (i.e., an “advisory firm review site”), and hire a steady stream of new advisors to expand their capacity if/when/as leads come in. The caveat, though, is that consumers tend to form connections with (and leave reviews for) their advisor as an individual (not the firm), most advisor review sites are built to highlight reviews at the advisor level (not the firm level), and when there are barely 1,000-plus RIAs with more than $1B in AUM in total, there are just only so many that may be willing to pay to engage in advisor reviews in the first place (and not necessarily enough to sustain an entire lead gen/advisor reviews platform). Which means in the end, it’s still not clear whether there’s not enough room in-between those groups for any kind of client reviews site to gain traction as a lead generation channel.

JOE DURAN PURSUING CAPITAL RAISE FOR RIA INVESTING BUSINESS WITH EMPHASIS ON LEAD GENERATION

Over the past decade, there has been a bevy of RIA “aggregators” eager to buy into the profitable economics of independent advisory firms. In the short term, firms (once they’re established) tend to have stable revenue and strong profit margins, while over the long run they often have at least a moderate baseline level of growth owing to clients’ portfolio contributions and market growth lifting firms’ assets under management (and consequently their revenues, profits and the firm owners’ return on their investment). All of which means that even an advisory firm that does little more to grow than to retain its existing clients can be an appealing target for acquisition.

Of course, most aggregators would probably like to buy firms that don’t rely only on existing clients for growth: Ideally, there would also be a steady flow of new clients to lift organic growth even higher (whom, as an added bonus, the aggregator may be able to serve more efficiently with its scale than the independent RIA would have on its own).

In practice, however, such firms have proven to be remarkably rare. Benchmarking studies have consistently shown advisory firms’ actual client growth rates on average to be only in the mid-to-high single digits — and although aggregators might be able to improve profitability by centralizing their firms’ administrative and back-office functions, there’s still a limit to how high a return they can realize on their investment if the organic revenue growth engine isn’t there to begin with. (For example, an aggregator that pays 2.5X revenue for a firm with a 7% annual growth rate and 30% profit margins would take seven years just to recover its original investment in profit distributions.)

Yet the irony is that the challenge of attracting and retaining new clients has only accelerated the pace of M&A in the industry in recent years, as firms flush with private equity capital that struggle to grow organically simply double down on inorganic growth via acquisition instead (even though the firms they target are as likely as not to have the same challenges around organic growth … which in turn just fuels even more M&A to further accelerate the inorganic growth strategy).

In turn, the challenge of attracting new clients organically has led to an explosion in demand for lead generation platforms, provided either by RIA custodial platforms or third-party services like Zoe Financial, SmartAsset and Dave Ramsey’s SmartVestor. These can be effective tools for finding and vetting prospective clients, particularly for firms (RIA aggregators among them) that have grown to the point where they have dedicated business development staff who can handle the follow-up and screening process for cold leads as they come in without using advisory staff time (and that have the capacity either to spread new clients among existing advisors or to hire new advisors when the need arises).

However, even for mega-RIAs that can effectively use lead generation platforms to create actual client growth, the cost of such platforms — typically a 25% revenue share over the lifetime of the client for all clients referred — means that advisory firms (which have profit margins of around 30% on average) are often giving up nearly all of their profits from clients referred by lead generation platforms on the cost of the lead generation itself. Meaning that even if the lead generation platform can boost growth in clients and topline revenue, very little of that growth actually comes back to the firm in the form of profits — which brings us right back to the issue of firms struggling to grow organically on their own, an issue that is only masked by capital-driven inorganic growth.

In this context, it’s notable that Joe Duran, who previously founded United Capital Financial Advisors (and subsequently sold it to Goldman Sachs in 2019, staying on until just before Goldman announced that it had sold its acquisition to Creative Planning last month), is reportedly looking to start a new venture to invest in RIA firms. Although nothing has been announced officially yet, it’s reported that the platform would have a particular focus on providing lead generation for its RIA investments to drive organic growth for its member firms (rather than ‘just’ trying to grow them by packaging together more and more acquisitions and sub-acquisitions).

Conceptually, the strategy makes sense: When investing in a firm, there’s only so much that can be streamlined in terms of operational efficiency, but there’s theoretically no limit to how much the firm can grow and scale — and since so many RIAs notoriously struggle with organic growth, that may be the most cost-effective direction to deploy capital. Because notably, even if Duran’s firm absorbs 100% of the costs of acquiring new clients — around $7,000 per client for an experienced advisory firm, per the most recent Kitces Research on Marketing — that amounts to 0.7X the revenue of a traditional $1M AUM client … which is only cost a fraction of the 25% of lifetime revenue that firms regularly pay to third-party lead generation platforms (which can amount to 7.5X revenue for a client that sticks around for 30 years!), or of the 2.5X to 3X annual revenue that acquirers typically pay for inorganic growth. In other words, by taking minority stakes in RIA firms and providing those firms with an in-house lead generation platform that merely replicates typical client acquisition costs but in a more scalable manner that isn’t constrained by the individual advisor’s time and capacity, Duran’s venture could realize a far better return on growth capital (acquiring clients at 0.7X revenue) than if those firms used that same capital on acquisitions (2.5X-plus of revenue) or third-party lead generation platforms (as much as 7.5X revenue). And if Duran’s firm can refine its lead generation process further and bring client acquisition costs down, so much the better.

The caveat, however, is that lead generation — especially scalable lead generation – remains an incredibly difficult task, particularly as firms scale regionally and nationally. Even firms that do achieve success in organic growth eventually reach a breaking point as their marketing strategies become saturated, driving up client acquisition costs in turn (and/or forcing them to constantly find new marketing channels to explore). Nonetheless, if Duran’s venture can exploit the difference between what aggregators typically spend on acquisition costs and/or third-party lead generation platforms, and what the firm can pay by just investing into its own marketing to grow organically (even at an average rate, before even considering any scaling effects of doing lead generation for multiple firms) it may represent an intriguing opportunity to scale up lead generation for RIAs without driving up client acquisition costs in turn, providing a substantial boost to enterprise value. (Though of course, the question remains how well Duran’s venture will handle solving the issue of marketing at scale to attract clients to its own lead generation platform. But given his track record at United Capital of integrating multiple M&A acquisitions under one technology platform, it will be worth watching to find out more.)

SECURITIZE ACQUIRES ONRAMP INVEST AS DIGITAL ASSETS CONTINUE TO LOSE STEAM AMONG RIAS

In the nearly 15 years since the launch of bitcoin, there have been three major peaks of interest in cryptocurrency (and the other various digital assets, like NFTs, that spawned in its wake). The first was in 2013, when cryptocurrency first entered popular discourse after its price spiked from $13 to over $1,100 (which was later found to have likely been the result of manipulative trades by a single person). The second was in late 2017, when another surge in the price of bitcoin — this time to above $20,000 — spurred a wide interest in sudden mania for blockchain technology, leading many companies to launch blockchain initiatives (or simply, in some cases, add “blockchain” to their name) to cash in on the hype. Finally, starting in late 2019 and picking up steam with the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic, cryptocurrency went through its third major surge, with bitcoin hitting an all-time high of over $68,000 in November 2021 and “web3” becoming an inescapable buzzword among business and technology circles.

Each time the interest in and demand for cryptocurrency spiked, a wide range of startups arose with the goal of making it easier for investors to own and trade digital assets. While these platforms boomed on the consumer-facing side (for better or for worse, as they lacked any of the controls imposed on banks and brokerage firms, and varied wildly in legitimacy and security), advisor adoption of cryptocurrencies was virtually nonexistent. In part, this was likely because advisors tend to bristle at the idea of “the next big thing,” which often sets off alarm bells amid memories of the 1990s tech and 2000s real estate bubbles. More practically, however, even advisors who may have been open to cryptocurrency struggled mightily to adopt it simply because cryptocurrencies aren’t available in the vehicles advisors traditionally use for investing (e.g., mutual funds or ETFs), nor are they compatible with the platforms advisors traditionally use for trading, custody and performance reporting.

As a result, a second wave of startups emerged around the crypto boom of 2019-2021 with the goal of solving crypto investing specifically for advisors, with their unique platform and integration needs. One of the most visible of these was Onramp Invest, which launched in 2021 to great fanfare driven by the popularity and visibility of its co-founder and original CEO, Tyrone Ross.

Onramp took a two-pronged approach to promoting cryptocurrency investing for financial advisors, aimed at solving what it saw as the biggest hurdles advisors faced to adopting it. First, it provided an education platform to familiarize advisors with digital assets, aiming to ease their anxiety with crypto as a technology and an asset class by building a foundation of knowledge and familiarity. Secondly, Onramp sought to bridge the gap between the traditional and crypto financial ecosystems, building an integration hub to help data flow from the “nontraditional” platforms where cryptocurrency assets were held into traditional advisor reporting systems, and eventually aimed to offer a more direct crypto investing capability where advisors could buy, sell and trade crypto assets directly through the platform.

However, as effective as Onramp may have been at breaking down what it saw as the barriers to advisors investing in cryptocurrencies, the biggest hurdle toward advisors’ adoption remained the asset class itself. The sheer volatility of cryptocurrency — where one of the most stable assets, bitcoin, has experienced 50% to 70% declines after each of its respective peaks — not to mention the highly publicized stories of scams and theft involving crypto assets (most notably the collapse of crypto exchange FTX, but also a host of smaller exchanges and individual cryptocurrencies) creates fiduciary issues, liability concerns and significant questions about cryptocurrency’s viability as a long-term investment. Even for advisors willing to allocate a small slice of clients’ portfolios, the work involved in building systems to do so — even if Onramp streamlined that process significantly — may have just not seemed worth it for an asset that might have made up 1% of a client’s portfolio.

These dynamics led to challenges for many crypto platforms, including Onramp. In early 2022, as the crypto bubble finally burst and asset prices crashed, Ross and several of Onramp’s other executives and board members left the company, which laid off employees as advisors and clients pulled their investments from the platform and capital opportunities dried up.

Now the news comes that Onramp Invest is being sold to alternatives investing platform Securitize after a year in which Onramp invested in new features such as offering qualified accounts but advisor interest in digital assets remained nonexistent. Securitize is a platform that is focused on investing not in cryptocurrency or other “purely” digital assets, but on providing access to private markets in asset classes like startup capital, commodities and real estate via a blockchain-based tokenization process. So while in a sense it aligns with Onramp’s original mission of providing opportunities to invest in digital assets, it does mark a shift in direction away from the cryptocurrencies that were Onramp’s main focus and toward a broader alternative assets approach (though still with a digital flavor, given Securitize’s use of digital tokenization).

From Securitize’s perspective, it’s clear that the acquisition is about finding a new distribution channel in the RIA community for its lineup of tokenized private funds. To wit, in its announcement of the Onramp acquisition, Securitize focuses not on crypto investing, but rather on bringing Securitize’s blockchain-based alternative investments platform to Onramp’s existing base of advisors. That makes sense because, unlike cryptocurrency, alternative investment asset classes have been gaining traction among financial advisors, with established providers like iCapital and CAIS competing with numerous startups to expand alternatives into the RIA market. Securitize’s blockchain-based tokenization approach gives it a unique and differentiated approach in this regard, particularly as it gives it some ability to offer lower investment minimums and more liquidity than most alternative assets. And Onramp’s existing user base is likely to be open to Securitize’s approach, given that those advisors clearly have an inherent interest in crypto and blockchain more generally.

From the broader industry perspective, the acquisition of Onramp by a provider without a focus on cryptocurrency seems to mark the end of a chapter (at least for now) for providers betting on a future of widespread cryptocurrency adoption among advisors (although Ross’s latest venture since leaving Onramp, Turnqey Labs, continues in this vein by aggregating cryptocurrency account data for integration into advisors’ technology tools). With the public’s attention having fully shifted from cryptocurrency to the next “next big thing” in AI technology, and with the SEC seeming unlikely to approve a spot bitcoin or other cryptocurrency ETF that would facilitate investing within a more familiar platform, it appears that innovation in this space is slowing down … at least, until the next crypto boom.

WEALTHTENDER PARTNERS WITH UNEST TO ACCESS MORE CONSUMERS DIRECTLY (BUT WILL IT BE ENOUGH TO BECOME ‘THE ONE’ ADVISOR RATING SERVICE?)

The release of the revised SEC Marketing Rule in 2021 reformed an extremely outdated rule that had prohibited financial advisors from using client testimonials in their marketing. The origin of the rule, however, was quite sound: At its core, it was about ensuring that advisors didn’t tout their clients’ investment returns in their advertising materials, recognizing that doing so was rife with potential for cherry-picking the best results without acknowledging that other clients weren’t necessarily likely to have the same outcome. But as the industry has shifted toward financial advice, with investing becoming more commoditized and focused around optimizing risk-adjusted returns through asset allocation rather than maximizing returns absolutely, the risk that advisors would use testimonials to highlight unrealistic outcomes — while not completely eliminated — has faded considerably.

Meanwhile, the Internet age has coincided with a huge increase in consumers’ desire to evaluate the quality of service providers via customer reviews. That created no small amount of tension with the old SEC rule, because while in other industries businesses could ask their customers to leave reviews on platforms such as Yelp or Google (and subsequently highlight the ‘best’ reviews on their own websites and social media platform), the SEC’s rule meant that financial advisors had no ability to request client feedback or highlight it in their marketing materials — until the SEC at long last updated the rule, finally acknowledging the evolution in how consumers seek out and evaluate services.

When the rule changed, a number of AdvisorTech startups emerged almost immediately, looking to replicate the established models of review sites in other fields that sought to make it easier for consumers to find a “good” professional among the many options out there — for example, Healthgrades for doctors, Angi for home repair professionals and Avvo for attorneys. And for these startups, speed mattered: The key to success for review sites in other industries was to gain enough market share early on to show up first in search results, attract the most eyeballs and user ratings, and ultimately become the place to go for reviews. The business model doesn’t really work unless there truly is one central platform, since the entire idea is to narrow down the options for consumers to the highest-rated professionals. Having multiple ratings sites introduces more, not fewer, options, so the whole thing breaks down if there isn’t one platform pulling in a dominant share of the reviews.

But if you’re looking to build a successful review site, not only do you need to convince consumers to leave reviews of the professionals they’ve hired after the fact — you also need to make sure that new customers can find your site when they’re looking to hire someone. One way to do this would be to focus on boosting search engine rankings to ensure that the site shows up at the top of the list of Google results for “best financial advisors” and similar searches; that’s why it made sense for WiserAdvisor, which has made SEO a core part of its strategy to bring consumers to its lead generation service, to acquire IndyFin and its client feedback tools. But the caveat there is that SEO is an ever-shifting, ultracompetitive landscape that can be upended by a change in the search engine’s algorithm.

Alternatively, another method that avoids the messiness of SEO would be to tap into an existing channel of consumers who are already likely to be in the market for a financial advisor, and put your advisor search-and-review platform in front of them — reaching consumers directly where they are rather than waiting for them to find you via search engine.

In this vein, it’s notable that Wealthtender, one of the advisor review/testimonial sites that emerged in aftermath of the SEC’s updated marketing rule, announced last month that it is partnering with UNest, a fintech platform that helps families open UTMAs for their minor children. UNest had previously been a purely direct-to-consumer tool, but in announcing the Wealthtender partnership, it also made it known that it is launching an advisor-facing version, dubbed UNest FinPro, for which Wealthtender will provide the platform to connect consumers on the UNest site with participating advisors.

From Wealthtender’s perspective, the partnership provides instant access to an existing base of consumers who have (or are considering getting) custodial investment accounts through UNest, and who might be seeking a financial advisor for guidance on planning and investing funds in the account. It’s an extension of a strategy Wealthtender has used before in partnering with consumer-facing enterprises to provide find-an-advisor tools built on its technology (as Wealthtender already powers find-an-advisor tools for both Onyx Advisor Network and the American Institute of Certified College Financial Consultants) — which presumably benefits Wealthtender both by earning revenue directly through its enterprise partnerships as well as by boosting the profile of its main platform as the go-to technology for advisor profiles and reviews.

On one hand, the deal further highlights how advisor review sites are still not an “if you build it, they will come” solution that will attain a critical mass of reviews and market share simply by existing on the Internet. With multiple competitors vying for the lead spot in advisor ratings (including the WiserAdvisor-owned IndyFin and the soon-to-be-released U.S. version of Unbiased), the economics of using SEO and paid advertising to climb the search engine rankings are grim, with everyone trying to achieve the top spot in a winner-take-all competition. To this end, getting directly in front of consumers who are already looking for an advisor by partnering with existing consumer-facing platforms makes a lot of sense.

On the other hand, it’s not clear whether a platform like UNest will prove to be a strong partner for further boosting Wealthtender’s service. For one thing, the platform’s core customer base — generally younger families creating small-balance investment accounts for their children — isn’t typically a domain that a large number of advisors serve. Furthermore, the brand that UNest has built as a direct-to-consumer platform means that many of its customers have self-selected as DIY investors who are comfortable opening their own accounts and managing their own investments, which means the typical UNest customer may not even be that interested in finding a financial advisor. Of course, there’s bound to be some interest in any customer base that’s big enough (and UNest claims to have served at least 700,000 parents and children, which is presumably enough to garner at least some interest in advisors who participate in UNest FinPro), but in the long run Wealthtender will likely need more — and bigger — enterprise partnerships to generate enough volume in its lead generation business to scale further.

That ultimately just further reaffirms the challenging reality that as much as lead generation platforms focus on the quality of their advisor matching and their capabilities in showing reviews, the question of how the lead generation platforms themselves attract quality prospects — to the extent that advisors take notice and sign up — is still an open one.

FEDERAL AND STATE REGULATORS INVESTIGATE RIAS’ AND BROKER-DEALERS’ USE OF AI

Over the past year there’s been a fresh wave of discussion about artificial intelligence and its potential to replace humans in an ever-widening range of jobs, including conceivably (if not terribly likely) even financial advice. Epitomized by tools like ChatGPT, AI is reaching the point where it can imitate human language well enough to pass for a real person in some contexts — but at its core, AI is only as smart as the humans who program it have trained it to be.

For example, there’s often an impression that, being based on computers and code, AI is free from the biases that humans are subject to. But the reality is that because it’s programmed by humans and trained on a dataset of human-created language, not only is AI subject to the same biases as its developers, but those biases are often amplified in the absence of any self-consciousness or willful effort to tamp them down. Examples of bias based on race and gender have already shown up in contexts like hiring software, facial recognition and decision-making in health care — not because those platforms’ developers were trying to bias the software in any way, but simply because the data it was trained on contained trends that caused it to favor one group over others.

While most examples of bias in AI seem to have been the unintended consequence of training on a biased data set (and failing to recognize or correct for those biases in the data), there nonetheless remains the possibility that some AI tools could intentionally be programmed and trained by their developers to favor certain outcomes — either at the preference of the developer themselves, or that of the company that creates the AI tool. In the financial services context, for instance, it’s plausible to imagine a company that sells financial products and solutions creating and distributing technology to advisors that favors its own products over others. Yet for financial advisors who have a fiduciary obligation to give advice in their clients’ best interests, that obligation extends to any technology that they use to generate recommendations. That means that financial advisors are effectively required to vet their technology tools — including those driven by AI — to ensure they meet the same fiduciary standard as if the advisor were giving the recommendation on their own.

It’s notable, then, that in August, both the Securities and Exchange Commission and Massachusetts Secretary of State William Galvin (who has garnered a reputation as one of the more actively pro-consumer state securities regulators) signaled their concerns about the use if AI in the financial services industry, particularly with the ways it represents a potential conflict of interest for advisory firms who use it. The SEC issued proposed regulations that would effectively require advisors to review the technology they use to analyze or recommend financial products or strategies for potential conflicts of interest, and to “eliminate or neutralize” those conflicts if they exist. Galvin, meanwhile, has taken a more targeted approach, sending a letter to six companies representing different areas of the financial services ecosystem (including JPMorgan Chase and Morgan Stanley, broker-dealer and trading platforms Tradier Brokerage and US Tiger Securities, RIA platform Savvy Advisors and marketing/client engagement platform Hearsay Systems) requesting details on how they use AI in their respective businesses.

What’s interesting about Galvin’s approach in particular is that it goes beyond just the mega-sized companies and platforms that target consumers directly to highlight firms such as Savvy Advisors (which provides a technology-forward RIA platform for advisors to build their business on, and which in July announced a new AI-driven tech platform) and Hearsay (which doesn’t directly serve advisory clients at all but instead provides social media and other marketing solutions). While it’s ultimately on advisors to ensure that their fiduciary obligations are met (and indeed, the SEC’s proposed regulations put the onus of vetting technology and eliminating conflicts of interest squarely on the advisor), the reality is that the sheer amount of technology used by advisors (with the median advisor using technology to support 15 separate business functions, per the most recent Kitces Research on AdvisorTech) means the time it would take for many RIAs to vet and audit their full suite of technology (and continuously do so as new features and updates are introduced) would quickly become overwhelming — meaning that without the some role for the technology providers themselves in ensuring the accuracy and objectivity in their software, it may be impractical to expect RIAs to shoulder the entire compliance burden on behalf of the technology they use.

Ultimately, the shape that AI takes in the financial industry may hinge on the ability and willingness of software providers to provide some degree of transparency, allowing advisors (and regulators) behind the curtain, so to speak, to see how recommendations are derived. On the one hand, it seems entirely reasonable for regulators like the SEC to highlight the fact that RIA firms are accountable to meet their fiduciary obligations (meaning that no matter what channel they deliver advice through, the firm is required to ensure that its advisors give advice in best interest of their clients, regardless of whether the advice itself is delivered by human or AI). On other hand, the emerging regulations around AI introduce real practical concerns for advisors — the most significant being how, with most calculations and analysis happening in a “black box” out of sight to everyone on the outside, the advisor would even know how to determine whether the technology they’re using is really objective. If it’s impossible to vet and test every recommendation (or if doing so becomes so time-consuming as to negate any time savings from using the technology to begin with), advisors may ultimately decide that it would be faster and safer to eschew the AI and stick with old-fashioned “human” advice.

Still, it seems inevitable that at some point at least some elements of advice will be increasingly driven by AI, or at least by sophisticated algorithms that focus client conversations and simplify the decision framework for clients. In the meantime, the growing scrutiny on the objectivity of AI-powered advice — while arguably well-founded from perspective of consumer protection (which, after all, is the purpose that federal and state securities regulators serve) — seems likely, at least in the short term, to push AI technology away from the advice segment and into more roles supporting advisors’ back-office needs, where the focus can be on automating processes and workflows without putting firms at risk for betting on the objectivity of AI-assisted advice.

A NEW, HIGHLY RATED ‘NEXT-GENERATION’ TECH STACK IS CREEPING UP ON ESTABLISHED ADVISORTECH INCUMBENTS

Advisors, and the financial services industry as a whole, don’t tend to live on the bleeding edge of technological innovation. In part this is because, being in a highly regulated industry with high standards for consumer protection, the “move fast and break things” ethos of many tech startups just doesn’t fit the AdvisorTech marketplace as well as it does in areas like social media, where new initiatives are constantly being tested on users (and often just as quickly abandoned). But the second reality is that most advisory firms simply don’t grow that fast organically (with most firms experiencing only single-digit client growth rates each year), while at the same time client retention rates are high, meaning that much of an advisor’s client base stays the same from one year to the next. That means that as long as everything is working correctly (and therefore isn’t at risk of getting the advisor sued), there isn’t much need for advisors to make big changes to their technology infrastructure very often. Indeed, the latest Kitces Research on AdvisorTech found that fewer than 5% of advisors intend to change their technology in any one software category next year, which averages out to core tech systems only changing an average of every 20 or so years for any given advisor.

The upshot of advisors’ relative preference for stability in their technology providers is that vendors that become market leaders tend to hold their incumbent status for a very long time. Over past 10 to 15 years, a coterie of incumbents formed that became the long-established leaders holding a dominant market share in all major AdvisorTech categories — including MoneyGuide and eMoney for financial planning software; Redtail for CRM; Orion, Black Diamond and Envestnet Tamarac for portfolio management and performance reporting; and Morningstar for investment research. Against this slate of incumbents, new startups have entered and tried to gain market share, but historically have had only limited success in doing so — because as noted earlier, advisors don’t have reason (or desire) to change their technology very often (while at the same time, the longer the current market leaders remain established, the more risky it seems to switch to a relative newcomer). In order to convince advisors to go through switching costs of migrating data, reconfiguring systems and processes, and training team members, the new software needs to be much better than the incumbent — enough to get advisors not only to adopt it and absorb the switching costs of doing so, but also to spread the word about it to others who might be more reluctant to do so.

That makes it notable that another key finding from the latest 2023 Kitces Research on AdvisorTech is that a new cluster of technology tools is emerging as an alternative “next-generation tech stack” that appears to be gaining market share from the long-established incumbents on the strength of superior satisfaction and value ratings from advisors. This new, next-generation tech stack includes tools like RightCapital for financial planning software, Wealthbox for CRM, Advyzon for performance reporting and YCharts for investment research, all of which have materially higher satisfaction and value ratings than the category incumbents they’re usurping:

Alongside these tools that are coming to define the next-generation advisor core tech stack, other tools are rising to gain significant adoption in more specialized planning software categories that were previously little used by advisors, reflecting the continued shift for advisors into deeper advice and planning. The standout example here is the growth of the specialized tax planning software category, where the overall category adoption rate nearly doubled, from 36.9% in 2021 to 61.7% in 2023, mainly on the strength of Holistiplan and its 9.3 satisfaction rating. But the specialized retirement distribution planning category also saw a large uptick in adoption (24.8% to 49.9%), led largely by Income Lab (with a 9.0 satisfaction score), and the non-AUM fee billing category — which didn’t exist as its own category in 2021 — rose to a 36.9% adoption rate as advisors increasingly turned to AdvicePay to charge stand-alone financial planning fees. In other words, in addition to the core AdvisorTech tools like financial planning, CRM and performance reporting, it’s becoming increasingly common to also adopt one or more of a number of specialized planning tools for tax or retirement (not to mention other categories like Social Security, student loan and stock options planning) — and to charge an advice fee (e.g., annual retainer or monthly subscription) for all of that comprehensive planning, for which another (scalable billing) tool is needed!

The examples highlighted above are all the more impressive given the reality that advisors don’t tend to change technology often, so it takes a truly standout piece of software to convince a lot of advisors to adopt it all at once. And the reality is that in most software categories where there is an established incumbent, a newcomer may be lucky to chip away 2% to 3% of market share each year. But as examples like RightCapital — which has crept up in market share steadily, gaining about 3% market share per year for each of the past seven years, to the point where it has almost overtaken the long-tenured MoneyGuide in adoption rate amongst independent advisors — show, even if a tool doesn’t win an onslaught of new business all at once, a long enough track record of high satisfaction can lead to enough gradual adoption that the “startup” solution eventually is the incumbent. And in that vein, the highly rated members of the next-generation tech stack have all the makings of what the next generation of incumbents will look like (which, it must be said, generally bodes poorly for the current incumbents in the space).

Going forward, the biggest opportunity for growth among new technology vendors — particularly in the core categories with long-entrenched incumbents — is still among new RIAs that form or go independent from broker-dealers, and thus are actively in the market for all of their tech at once and have no “incumbent” to switch from. It follows that the vendors who are the most highly rated by other advisors are the most likely to win this new business, which further suggests that the new crop of highly rated vendors are the best positioned to capture this growth in the years ahead. The key, though, is simply to recognize that shifts in AdvisorTech leadership never happen “virally,” with fast switching from an existing provider. Yet at the same time, the steady drip of growth from a rising star can cumulatively snowball into a massive shift in leadership in any particular AdvisorTech category over a seven-to-10-year time period.

In the meantime, we’ve rolled out a beta version of our new AdvisorTech Directory, along with making updates to the latest version of our Financial AdvisorTech Solutions Map (produced in collaboration with Craig Iskowitz of Ezra Group)!

So what do you think? Is an effective lead generation service worth giving up potentially 25% of the lifetime revenue from referred clients? Is there a path for digital assets to become widely adopted by advisors, whether in the form of cryptocurrency or tokenized private market investments? How easy (or hard) would it be to comply with the SEC’s regulations around AI in AdvisorTech? Let us know your thoughts!

Michael Kitces is the head of planning strategy at Buckingham Strategic Partners, co-founder of the XY Planning Network, AdvicePay and fpPathfinder, and publisher of the continuing education blog for financial planners, Nerd’sEye View. You can follow him on Twitter @MichaelKitces.

Ben Henry-Moreland is senior financial planning nerd at Kitces.com, where he researches and writes for the Nerd’s Eye View blog. In addition to his work at Kitces.com, Ben serves clients at his RIA firm, Freelance Financial Planning.